The Pattern Language of Project Xanadu

Budding

🌿Planted Jul 10, 2020 –

Last tended Jun 17, 2021

Design

The Web

Digital Gardening

When it comes to visionary, before-its-time software, it's hard to find a better archetype than Ted Nelson's

It's infamous in the technology community as a sixty-year project that never quite launched. A cautionary tale of what happens when you overhype, underdeliver, and try to stuff an operating system's worth of features into a single piece of proprietary software. The kind of tale that makes our ferociously lean startup culture of Move Fast, Break Things, and Demo or Die seem almost sensible.

Xanadu was a hypothetical hypertext system. The word hypothetical is a bit strong. Many versions were built. There is a working demo showcasing a few of its features

It's hard to read the word hypertext in 2021 and not believe its synonymous with the system Tim Berners-Lee built in 1989 – the World Wide Web that became so much more than linked text on digital screens. The version of hypertext you are reading this on is the only hypertext most of us have ever known.

And yet the idea of hypertext predates Berners-Lee by two decades. The term was coined in 1963 by none other than Ted Nelson as part of a much larger vision; one small brick in the grand Xanadu dream mansion. While Nelson coined the word, the notion of linked documents goes back to Jorge Luis Borges The Garden of Forking Paths" in 1941 and Vannevar Bush's Memex machine in 1945 – both significant, named influences for Nelson.

To talk about Xanadu, we need to put a pin in our current understanding of hypertext. Our preconceived notions of what a link is, how it works, and what digital text is capable of threatens to overwrite the alternate history we're about to explore.

Ted hoped it would be a medium for "

Xanadu's failure to mature into a widespread, useable commercial product is great fodder a

Yet these historical skirmishes and financial flops are also the least interesting thing about Xanadu. The most interesting part is its Pattern Language.

Architectural Pattern Languages

They come from the land of architects: the software developers of the material world. Namely, the architect

Alexander defined 253 architectural patterns for designing cities, towns, and homes. These became the example patterns for writing patterns. Each one is composed of a context, problem, example, and solution.

For example, the design pattern A Place to Wait asks that we create comfortable accommodation and ambient activity whenever someone needs to wait; benches, cafes, reading rooms, miniature playgrounds, three-reel slot machines (if we happen to be in the Las Vegas airport). This solves the problem of huddles of people awkwardly hovering in liminal space; near doorways, taking up sidewalks, anxiously waiting for delayed flights or dental operations or immigration investigations without anything to distract them from uncertain fates.

There's no single way to implement these design patterns. They are purposefully abstract enough to adapt to the situation at hand. Rules of thumb rather than sets of formulaic instructions.

Xanadu as a Design Pattern

Taken as a collection of design patterns, Xanadu's documentation suggests solutions to some of the hypertextual problems we're wrestling with today;

- How do we structure information and build relationships between pieces of data that help us see them across contexts, and clarify understanding?

- How do we build systems that allow people to collaborate on shared documents without losing authorship? How do we credit and compensate authors based on their contributions?

- How do we bring ideas and data from a variety of sources into conversation with our own, while leaving a clear trail back to the origin?

Xanadu became a sad parable, when it should have been a piece of speculative design. A set of seeds scattered into the wind for other people to pick up and plant, rather than the patent-happy industrial farming conglomerate it tried to grow into.

Curiously enough, there appear to be rogue seedlings sprouting around the web. A number of Xanadu's design patterns are showing up in modern manifestations. We're finding ways to backwards engineer the original spirit of Xanadu into the existing structures of the World Wide Web.

The Patterns

1. Visible Links

Ted Nelson has many gripes, and jump links are one of his biggest. They're the kind of links we all use around the web today. Clicking a hyperlink is a bit of a gamble. It jumps you into somewhere unknown. You find out when you get there.

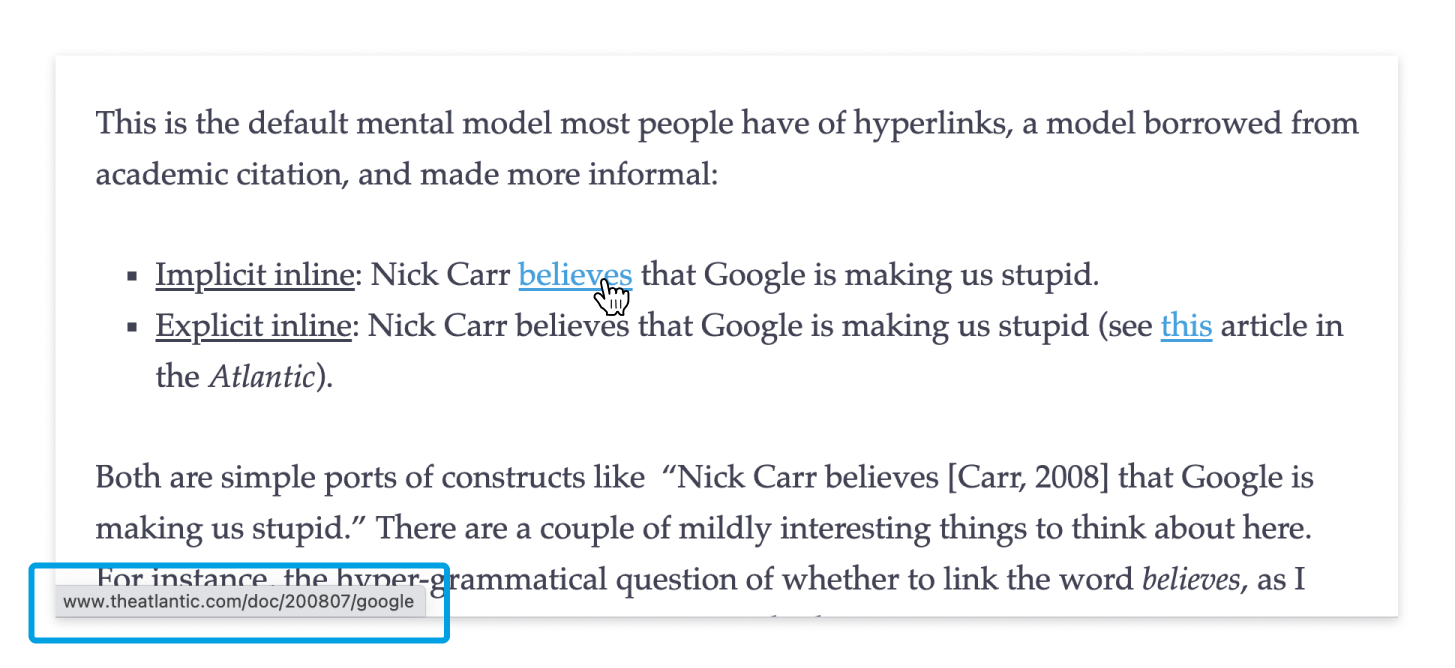

We've found ways to adapt to this; Venkatesh Rao has a compelling exploration of the

These can only tell you so much when modern URLs are often obscured by link shorteners and overstuffed with tracking queries. These solutions are only a band-aid on the underlying wound. They suggest where you're headed, rather than showing you.

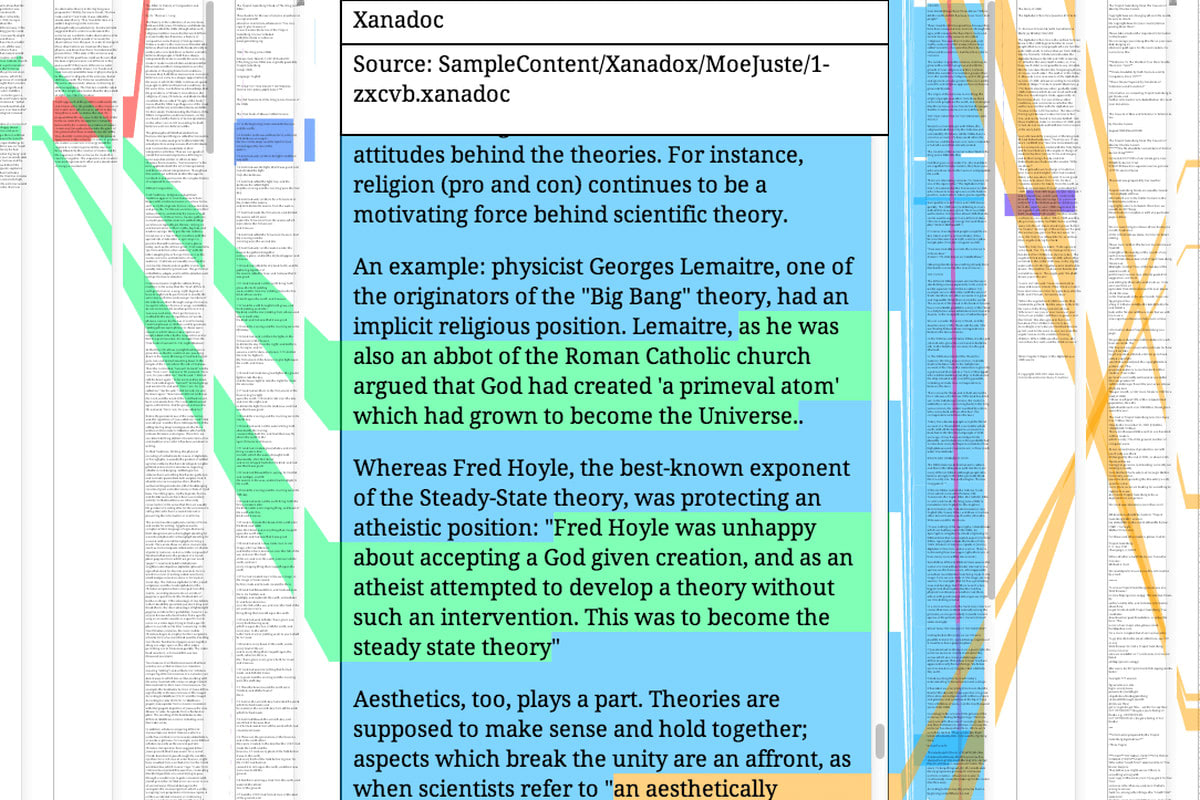

Nelson's answer to jump links are visible links – links that show you the full context of where you're headed. These were an essential feature of Xanadu. In the original mockups for "Xanadocs" linked text would be connected to its source in a rather literal fashion: brightly coloured highlights running between documents.

One of the original UI mockups for a Xanadoc with visible links between text blocks

This proposed solution relies on two other patterns – parallel documents and transpointing windows (covered below) – but the underlying principle was simply that links made their destinations clear.

In lieu of Xanadoc links, the modern web has landed on some fairly decent solutions to this issue: hover previews and unfurls.

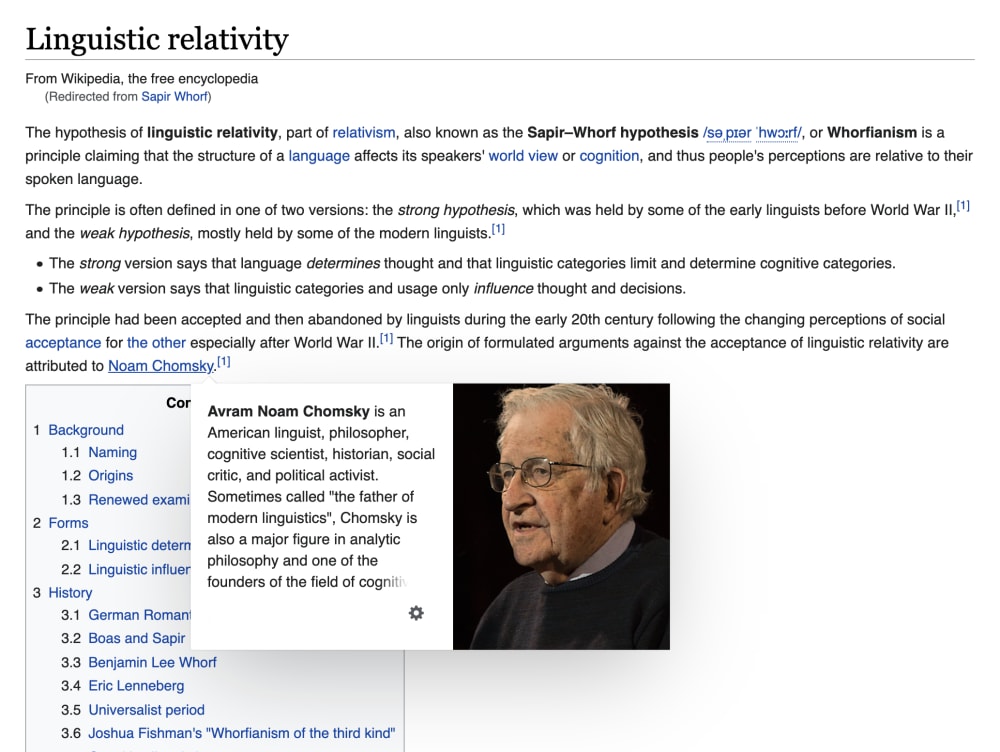

Hover previews are when you can see a preview of the page you're headed to when you hover over a link. It's usually an excerpt that gives you the page title, the first few lines of text, and sometimes an image. Wikipedia was one of the first major sites to

Wikipedia's interface showing one of the hover previews that appear over links

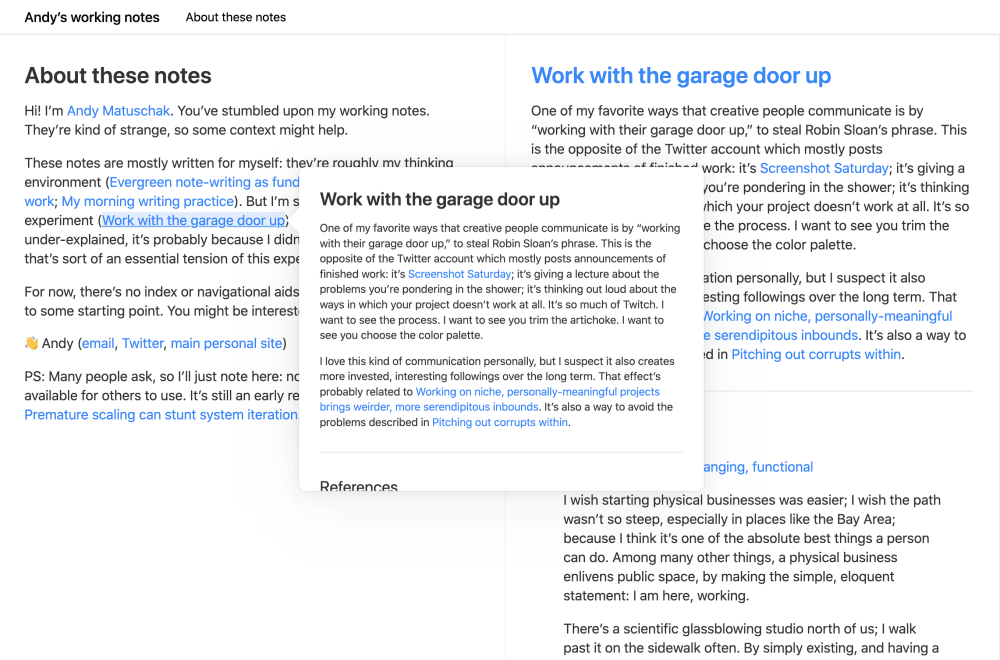

Hover previews have also become popular in the

Andy Matuschak's notes website featuring hover link previews

Similar to hover previews, unfurls are the preview cards that automagically appear when you paste a link into Twitter, Facebook, Notion, Miro, or any other richly-featured web app. If I paste a link to this great article on

Open graph previews appear in Notion when you paste a link and select 'Create Bookmark'

This system is powered by the

Both hover previews and link unfurls give you a good sense of where you're headed if you click on a link. They get us to semi-visible links.

Previews aren't quite the same as physical links between parts of a page though. You lose the fine-grained associations between specific paragraphs and lines. If we wanted to dial up the Xanadu-esque visibility, we could work on showing previews of the whole page and directing people to specific pieces of text within it.

Coming Soon

Feel free to bug me on twitter to finish writing this.

2. Parallel Documents

Side-by-side, interactive windows

Separate browser or application windows arranged side-by-side don't cut it

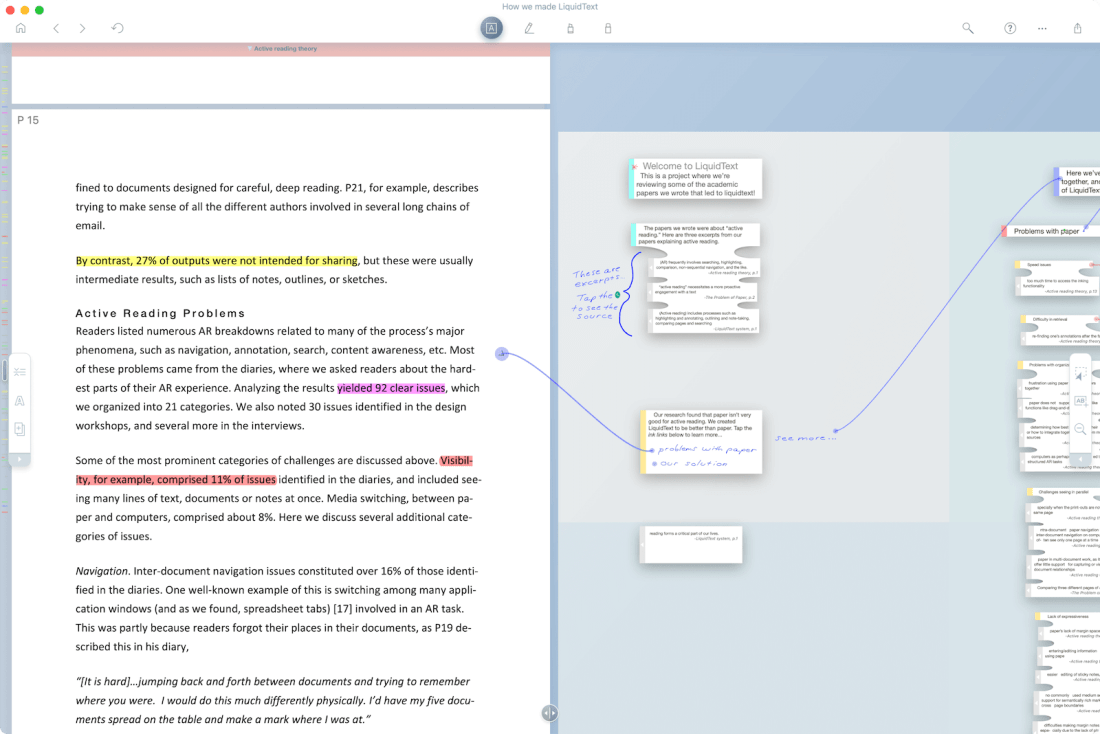

3. Transpointing Windows

Parts of documents visibly point to other parts

LiquidText

The interface of LiquidText with transpointing between sections of text

"parallel pages, visibly connected"

— Azlen Elza (@azlenelza)pic.twitter.com/JyhsFHz67HJune 15, 2020

4. Transclusion

5. Bi-directional Links

6. Version Control

In the age of Git, we tend to take version control for granted.

The first version control system dates back to

7. Modular Text Blocks

The core building block of the web has always been documents. While the idea of a webpage has evolved far beyond it's original idea, we still construct, connect, and navigate websites at the page level.

The early web was built for academic researchers to share their work, in a time before all the plebs invaded with our bleeding-heart livejournal entries, dancing baby GIFs, and TikTok moves. These researchers designed the system to mimic their primary medium of communication; paper-based academic articles and documents.

This paper document design metaphor determined many of the early architectural decisions. URL addresses were set at the page level, rather than the paragraph. Inline images were an afterthought, and even a contentious addition to the spec. No one seriously considered the possibility of adding videos or animations. The presumption visual images are a impoverished medium for serious intellectual thought is a whole other kettle of fish.

Blocks construct documents

Notion pioneered this in the note-taking space

Explosion of note-taking apps using a block-first approach: Roam, Innos, Clover, Craft, Kosmik

8. Stable, Universal Addresses

The web enforces addresess on the document level rather than the block level

No stability at all, link rot everywhere

URL queries and subpaths

Roam block UIDs

9. Annotation

Google docs comments

10. Multiple Views and Spatial Arrangements

Graph previews are a weak version of this

Notion linked databases that offer various view types

Most modern dashboards offer multiple ways to view data

ZigZag format

11. Micropayments

Jarons Lanier's dreams in Who Owns the Future

The inescapable cost of transactions

Web Monetisation API, Coil

Grant for the Web

Graeber's money-as-debt, soft money, local currencies and DAOs

The original Xanadu vision was ambitious. Unreasonably ambitious. The above feature list is a small selection.

Perhaps you sense the problem.

Solving all the things all at once gets tricky.

Instead, what we're now seeing is the ad-hoc, decentralised manifestation of Xanadu in bits and pieces.

People are building Xanadu without knowing what Xanadu is.

Which is the essence of a good pattern language; true patterns evolve naturally within systems, and are found rather than crafted. Christopher Alexander's

In the grand scheme of things, 60 years isn't an extraordinary amount of time to spend solving a problem. It's about 0.09% of history since humans first started creating symbolic cultural artefacts Using

Who knows, maybe Xanadu can still happen (if you clap for it) ✨

Linked References

A Short History of Bi-Directional Links

With the recent rise of Roam Research , the idea of bi-directional linking is having a bit of a moment. We're all very used to the mono-directional link the World Wide Web is built around. They…

Transclusion and Transcopyright Dreams

In 1965 Ted Nelson imagined a system of interactive, extendable text where words would be freed from the constraints of paper documents. This hypertext would make documents linkable. Twenty years…